Although it’s somewhat new to the public at large, the medical community has known about Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) for a long time. It’s a progressive neurological disease that was originally known as “punch-drunk syndrome” and was relegated to boxers (dementia pugilistica), as implied in its name. It is the result of repeated injury to the brain. Over the last 15 years, it’s made its way into the public consciousness since being discovered en masse in NFL players by Dr. Bennet Omalu.1 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y2GsZRTW6XE Notable examples include Hall of Famer Mike Webster who died at age 50, and whose autopsy revealed the first clinical proof of CTE in football players. More recently, the case of Aaron Hernandez was in the news. The neuroscientist who analyzed Hernandez’s brain after he died confirmed that he suffered the worst case of CTE ever seen in someone so young, with severe damage to regions that affect memory, impulse control, and behavior. This was particularly notable because the 27-year-old former New England Patriots player was implicated in the murders of two people outside a Boston nightclub simply for bumping into him while inside the club–as well as committing suicide in April 2017 while serving life in prison for a third murder. Both the murders and the suicide are likely related to the CTE.

Pathologically, the neurological deterioration associated with CTE is accompanied by atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes and accumulation of tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles. As it progresses, it is characterized by short-term memory loss, concentration deficits, confusion, depression, behavioral and personality changes (such as an increase in irritability, impulsivity, aggression, and thoughts of suicide), speech and gait abnormalities, Parkinsonism, and dementia.

Now, this explains what we know about the disease…or at least what we thought we knew. But in truth, the mechanisms underpinning concussion, traumatic brain injury, and chronic traumatic encephalopathy, and the relationships between these disorders, are poorly understood. Two recent studies reveal that the problem is far worse than we thought and is brought on by many more activities than we imagined. And in fact, as you will see, many parents have moved their children away from football in an effort to protect them–only to move them into sports that may be almost as damaging.

Many parents have moved their children away from football in an effort to protect them–only to move them into sports that may be almost as damaging.

Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model

The first study we’re going to look at was published just last month in the journal Brain. It concluded that focusing on the link between concussions and CTE is likely misguided.2 Chad A Tagge, Andrew M Fisher, Olga V Minaeva, Lee E Goldstein, etc. “Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model.” Brain, awx350, 18 January 2018. http://academic.oup.com/brain/advance-article/doi/10.1093/brain/awx350/4815697 The study found that it’s “hits to the head”– even ones that do not lead to concussions — that cause CTE in contact-sport athletes, members of the military, and others who suffer repetitive head trauma. As one of the authors of the study, Boston University Professor of Neurology and Pathology Ann McKee, said, “We know from our own pathologic work that about 20 percent of the brain donors with CTE never had a concussion, so there’s always been a bit of a disconnect between concussion and the development of CTE.” The key to preventing CTE, then, lies not in preventing and monitoring concussions but in preventing all hits to the head. This means that the NFL’s “concussion protocol” for dealing with in-game concussions is essentially meaningless–at least when it comes to protecting players from CTE.

The first study we’re going to look at was published just last month in the journal Brain. It concluded that focusing on the link between concussions and CTE is likely misguided.2 Chad A Tagge, Andrew M Fisher, Olga V Minaeva, Lee E Goldstein, etc. “Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model.” Brain, awx350, 18 January 2018. http://academic.oup.com/brain/advance-article/doi/10.1093/brain/awx350/4815697 The study found that it’s “hits to the head”– even ones that do not lead to concussions — that cause CTE in contact-sport athletes, members of the military, and others who suffer repetitive head trauma. As one of the authors of the study, Boston University Professor of Neurology and Pathology Ann McKee, said, “We know from our own pathologic work that about 20 percent of the brain donors with CTE never had a concussion, so there’s always been a bit of a disconnect between concussion and the development of CTE.” The key to preventing CTE, then, lies not in preventing and monitoring concussions but in preventing all hits to the head. This means that the NFL’s “concussion protocol” for dealing with in-game concussions is essentially meaningless–at least when it comes to protecting players from CTE.

The study also found that CTE likely begins earlier than previously thought–years before there are any outward signs of its onset.

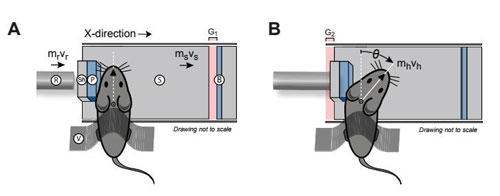

The study first examined post-mortem brains from teenage athletes in the acute-subacute period after mild closed-head impact injury and found astrocytosis, myelinated axonopathy, microvascular injury, perivascular neuroinflammation, and phosphorylated tau protein pathology. In simple English, they found a lot of damage to brain tissue. To investigate causal mechanisms, the researchers developed a way to mimic what happens to the human brain when you cause the brain of a mouse to “rattle” inside its skull–but at non-concussion levels. Specifically, the researchers wanted to look at sports-related injuries that are considered much milder than those that result in concussion. Researchers used an air cannon to propel a small object/slug against a mouse helmet to make the mouse’s head move in the same way as in a football helmet-to-helmet hit.

A diagram featuring mice and showing part of the experiment conducted by Goldstein and his team of researchers.

(Courtesy Boston University School of Medicine)

Stunningly, every single time they ran the experiment, they got CTE pathology, and they always got some degree of concussion–and sometimes, even, post-traumatic seizures. But, as bad as that is, that’s not the disturbing part.

According to lead researcher, Dr. Lee Goldstein, it’s not the severity of concussion that matters. It turns out that any jolt to the head causes damage. The level of CTE risk is determined by your age and how long you play (i.e., the number of jolts you receive over time). The younger you start and the longer you play, the greater your risk. “We see [CTE] even after one exposure to the impact, and it not only persists, but it will progress. It spreads through the brain. It will spread as you age.” He went on to say, “The concussion is actually a different mechanism from the mechanisms that lead to CTE. We can completely dissociate them. We can have CTE with or without a concussion. It’s somewhat irrelevant.”

We see CTE damage even after one exposure to impact, and it not only persists, but it progresses. It spreads through the brain. It spreads as you age.

If the study we’ve been talking about is correct–that concussions aren’t the problem; repetitive head trauma is–then we should see signs of CTE in a sizeable number of soccer players as the result of constantly heading the ball, yes?

Soccer and CTE: The Jury Is Out, but the Signs Aren’t Good

When it comes to CTE and soccer, the problem is that things are much where they were 15 years ago with American football: people haven’t connected the dots yet; there’s very little data yet to support the case; and there’s a multi-billion-dollar sport heavily invested in making sure that any possible connection is suitably downplayed.

Whereas Mike Webster’s death in 1990 was the watershed moment for CTE in American football, Jeff Astle’s death may have been that moment for soccer. Astle, who died in 2002, was posthumously diagnosed with CTE in 2014. (Postmortem investigations are the only definitive way to identify CTE.) During his career, he was considered by many to be the greatest “header” to ever play the game.3 http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lpxWOmzE3Rs

Astle’s death was a major factor in the initiation of a study published in 2017 that investigated the lifestyles and career paths of 14 deceased soccer players who suffered from dementia, 12 of whom died of advanced dementia.4 Helen Ling,Huw R. Morris,James W. Neal,et al. “Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players.” Acta Neuropathol. 2017; 133(3): 337–352. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5325836/ Only six of the families granted permission for postmortem examinations to investigate the cause of their dementia, but of those six, four were confirmed to have had CTE. All six also had symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, a form of dementia. That means that 2017 was the first time that CTE had been confirmed in a retired group of soccer players, which means that scientific data connecting soccer to CTE is running about 15 years behind American football. Although soccer players rarely suffer concussions VS American football players, they do sustain numerous minor blows to the head hitting other players, the ball, or goalposts…thousands of times a year, year after year.

According to the Jeff Astle Foundation, this represents just the tip of the iceberg. According to their estimates, more than 250 former professional soccer players have suffered some form of neurodegenerative disease as a result of playing “the beautiful game.”5 “‘250 more’ footballers with degenerative brain disease.” BBC News. 12 April 2016. (Accessed 27 Jan 2018.) http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-nottinghamshire-36015489 According to Astle’s daughter, who started the Foundation in 2014, this is “The tip of a very big iceberg, sadly. I wish it wasn’t, but I think it is.” She went on to clarify that remark by saying, “About 95% of the players affected have Alzheimer’s disease or had it before they died, while the rest have had other degenerative brain diseases.”

And Dr. Omalu, who has turned his attention from American football to soccer, agrees.6 Tully Corcoran. “The Famous CTE Doctor Is Coming After Soccer Now.” thebiglead. October 15, 2017. (Accessed 28 Jan 2018.) http://thebiglead.com/2017/10/15/the-famous-cte-doctor-is-coming-after-soccer-now/

“The soccer industry should stop denying the truth. They should say: soccer is not a high impact, high contact sport, but you could suffer brain injury in sports. You need to be aware of that. You need to play safe, like removing heading from play.”

Now, to be fair, the study is not without its flaws–most notably that it cherry picks its data. It didn’t look at “all” soccer players who had died, but rather a select group of soccer players who all died after exhibiting evidence of brain damage and dementia. Also, the balls used to play soccer today are much lighter than those used in the 1960s when Astle was playing, but they still pack a punch. Soccer balls can travel at speeds as high as 34 miles per hour during recreational play and more than double that during professional play. Head a soccer ball coming at you at 70 mph, and you’ve just given your brain a good-sized jolt.

It’s also worth noting that this study is hardly an outlier. Back in 2012, we talked about a study that was published in the journal Radiology that found that players who often head a soccer ball are at risk for developing a brain injury.7 Michael L. Lipton, Namhee Kim, E. Zimmerman, et al. “Soccer Heading Is Associated with White Matter Microstructural and Cognitive Abnormalities.” Radiology. 2013 Sep; 268(3): 850–857. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3750422/ For kids on a team who practice and play several times a week, heading the ball is part of their training, and they may do quite a bit of it. The research, which took place at Montefiore Medical Center in Bronx, New York, was based on brain scans of 32 participants who are regular soccer players, but not professionals. Using diffusion tensor imaging, the scientists were able to obtain a good view of both brain and nerve tissue. The instances of damage to the brain that turned up on the scans were much like those exhibited by patients diagnosed with a concussion.

The subjects reported how frequently they tend to head the ball when either practicing or playing a game. The researchers found that damage to the brain only seemed to show up in those who were heading the ball more than 1,000 times per year. While that may sound like an excessive amount of times to be smashing your head with a ball, it is not all that much heading for a player on a year-round team. Competitive teams play well beyond the fall season — often all year long — and this level of play can start for kids as young as nine years old. And even for those kids who don’t play year-round, a simple “heading drill” can result in dozens of high risk contacts in as little as five minutes.

Those volunteers who headed the ball often had scans displaying trauma to five areas of the brain. It affected both the front and the back portions of the brain, doing damage to regions that control a wide variety of functions such as memory, attention, and higher-order visual processing. When the scans were followed up by cognitive testing on the participants, those with signs of brain injury did noticeably worse. Their verbal memory scores and reaction times were lower than those who did not frequently head the ball.

The problem doesn’t seem to stem from any one individual instance of impact between the head and the ball. Rather, in line with the study that we talked about at the top of the newsletter, it seems to be the result of a cumulative effect on the nerve fibers of the brain that may ultimately damage and kill off brain cells. And in some cases, it may be years after playing soccer regularly before the damage becomes apparent.

Conclusion

So, what have we learned? Essentially two things:

- Repetitive trauma, not necessarily concussion, is the key to long-term brain damage

- The younger you are when you experience the trauma, the worse the long-term consequences for your brain

Repetitive trauma, not necessarily concussion, is the key to long-term brain damage.

With that in mind, as it relates to your children…

Football

As Chris Nowinski, the chairman of the Concussion Legacy Foundation and one of the authors of the study, said, “It will make a world of difference for your child’s experience in playing the game of football if you actually delay the onset of tackling, which now will involve hundreds of hits to the head, until their brain has had a chance to develop and until their body is really ready for tackle.” Unfortunately, that goes against the recommendations that we’re getting from the NFL and the youth football industry.

That said, building on the science of the study, the Concussion Legacy Foundation is launching a campaign to get children under 14 to play flag football.

Soccer

In 2015, U.S. Soccer, the governing body for the sport in the United States, announced that there should be no heading for any players age 10 and under, while limiting the amount of heading during practice for those ages 11 to 13.8 “U.S. Soccer Provides Additional Information About Upcoming Player Safety Campaign.” U.S. Soccer. Nov 9, 2015. (Accessed 27 Jan 2018.) http://www.ussoccer.com/stories/2015/11/09/22/57/151109-ussoccer-provides-additional-information-about-upcoming-player-safety-campaign Unfortunately, although that directive took effect for those who participate in U.S. Soccer’s Youth National Teams and its Development Academy, those programs only represent a fraction of the more than 3 million kids who play the sport nationwide–split equally between boys and girls–according to the U.S. Youth Soccer Association.

Hockey

Like soccer, ice hockey has also recently come into the crosshairs of concussion research.9 Hänninen T, Parkkari J, Tuominen M, et al. “Sport Concussion Assessment Tool: Interpreting day-of-injury scores in professional ice hockey players.” J Sci Med Sport. 2017 Dec 12. pii: S1440-2440(17)31824-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29254676 , 10 Trofa DP, Park CN, Noticewala MS, Lynch TS, Ahmad CS, Popkin CA. “The Impact of Body Checking on Youth Ice Hockey Injuries.” Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Dec 5;5(12):2325967117741647. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29238733 , 11 Sollmann N, Echlin PS, Schultz V, et al. “Sex differences in white matter alterations following repetitive subconcussive head impacts in collegiate ice hockey players.” Neuroimage Clin. 2017 Nov 21;17:642-649. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709295/ Considering, it’s a high contact sport, with lots of blows to the head and brutal body checks that jar the brain, that’s hardly surprising.

This year, Nicole de Moulpied, a hockey mom, started a no-check hockey program after her son suffered a concussion, though not from hockey. De Moulpied said the BU study is probably a game-changer.

“And in terms of hockey, it [the just published study on repetitive head trauma] might influence the rule-makers to increase the age when checking is introduced,” she said.12 Fred Thys. “Hits Affecting The Head — Even Ones Without Concussions — Cause CTE, BU Study Finds.” WBUR January 18, 2018. http://www.wbur.org/commonhealth/2018/01/18/hits-not-concussions-cte-study “That sounds like a compelling reason to possibly make some changes. So, it’ll be interesting to see if this actually spurs some movement.”

Is There Anything We Can Do About It?

There are no supplements that have been proven to prevent or reverse CTE. That said, if I had experienced repeated head trauma, I’d consider supplementing with an L-carnosine based formula. Studies have clearly demonstrated that L-carnosine inhibits the aggregation of beta amyloid deposits and fibrils in the brain.13 Josephine W. Wu , Kuan-Nan Liu, Su-Chun How, et al. “Carnosine’s Effect on Amyloid Fibril Formation and Induced Cytotoxicity of Lysozyme.” Plos One. Published: December 11, 2013. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0081982 , 14 Attanasio F, Convertino M, Magno A, et al. “Carnosine inhibits Aß(42) aggregation by perturbing the H-bond network in and around the central hydrophobic cluster.” Chembiochem. 2013 Mar 18;14(5):583-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440928 While other studies have shown that beta amyloid deposits are one of the characteristics associated with CTE.15 Stein TD, Montenigro PH, Alvarez VE, et al. “Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.” Acta Neuropathol. 2015 Jul;130(1):21-34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4529056/ It’s hardly conclusive, but it seems to be the best we’ve got at the moment.

And for Parents Concerned their Children Will Fall Behind Athletically

It’s worth noting that a number of athletic stars either came late to the game, or played minimally until into their 20’s. For example:

- American Football16 Miri Elmaleh. “NFL Greats Who Started the Game Late.” FlipGive. March 31st, 2016. (Accessed 28 Jan 2018.) http://www.flipgive.com/stories/nfl-greats-who-started-the-game-late

- Soccer17 Alfie Potts Harmer. “Top 15 Late Bloomers In Soccer History.” TheSportster. 08.24.15. (28 Jan 2018.) http://www.thesportster.com/soccer/top-15-late-bloomers-in-soccer-history/

In other words, sparing your children’s brains from repetitive trauma until their brains are developed enough to better handle it may not cost them a chance to be athletic stars. But it very well may save them from years of memory loss, concentration deficits, confusion, depression, behavioral and personality changes, speech and gait abnormalities, Parkinsonism, and dementia.

References

| ↑1 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y2GsZRTW6XE |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Chad A Tagge, Andrew M Fisher, Olga V Minaeva, Lee E Goldstein, etc. “Concussion, microvascular injury, and early tauopathy in young athletes after impact head injury and an impact concussion mouse model.” Brain, awx350, 18 January 2018. http://academic.oup.com/brain/advance-article/doi/10.1093/brain/awx350/4815697 |

| ↑3 | http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lpxWOmzE3Rs |

| ↑4 | Helen Ling,Huw R. Morris,James W. Neal,et al. “Mixed pathologies including chronic traumatic encephalopathy account for dementia in retired association football (soccer) players.” Acta Neuropathol. 2017; 133(3): 337–352. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5325836/ |

| ↑5 | “‘250 more’ footballers with degenerative brain disease.” BBC News. 12 April 2016. (Accessed 27 Jan 2018.) http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-nottinghamshire-36015489 |

| ↑6 | Tully Corcoran. “The Famous CTE Doctor Is Coming After Soccer Now.” thebiglead. October 15, 2017. (Accessed 28 Jan 2018.) http://thebiglead.com/2017/10/15/the-famous-cte-doctor-is-coming-after-soccer-now/ |

| ↑7 | Michael L. Lipton, Namhee Kim, E. Zimmerman, et al. “Soccer Heading Is Associated with White Matter Microstructural and Cognitive Abnormalities.” Radiology. 2013 Sep; 268(3): 850–857. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3750422/ |

| ↑8 | “U.S. Soccer Provides Additional Information About Upcoming Player Safety Campaign.” U.S. Soccer. Nov 9, 2015. (Accessed 27 Jan 2018.) http://www.ussoccer.com/stories/2015/11/09/22/57/151109-ussoccer-provides-additional-information-about-upcoming-player-safety-campaign |

| ↑9 | Hänninen T, Parkkari J, Tuominen M, et al. “Sport Concussion Assessment Tool: Interpreting day-of-injury scores in professional ice hockey players.” J Sci Med Sport. 2017 Dec 12. pii: S1440-2440(17)31824-8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29254676 |

| ↑10 | Trofa DP, Park CN, Noticewala MS, Lynch TS, Ahmad CS, Popkin CA. “The Impact of Body Checking on Youth Ice Hockey Injuries.” Orthop J Sports Med. 2017 Dec 5;5(12):2325967117741647. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29238733 |

| ↑11 | Sollmann N, Echlin PS, Schultz V, et al. “Sex differences in white matter alterations following repetitive subconcussive head impacts in collegiate ice hockey players.” Neuroimage Clin. 2017 Nov 21;17:642-649. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5709295/ |

| ↑12 | Fred Thys. “Hits Affecting The Head — Even Ones Without Concussions — Cause CTE, BU Study Finds.” WBUR January 18, 2018. http://www.wbur.org/commonhealth/2018/01/18/hits-not-concussions-cte-study |

| ↑13 | Josephine W. Wu , Kuan-Nan Liu, Su-Chun How, et al. “Carnosine’s Effect on Amyloid Fibril Formation and Induced Cytotoxicity of Lysozyme.” Plos One. Published: December 11, 2013. http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0081982 |

| ↑14 | Attanasio F, Convertino M, Magno A, et al. “Carnosine inhibits Aß(42) aggregation by perturbing the H-bond network in and around the central hydrophobic cluster.” Chembiochem. 2013 Mar 18;14(5):583-92. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23440928 |

| ↑15 | Stein TD, Montenigro PH, Alvarez VE, et al. “Beta-amyloid deposition in chronic traumatic encephalopathy.” Acta Neuropathol. 2015 Jul;130(1):21-34. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4529056/ |

| ↑16 | Miri Elmaleh. “NFL Greats Who Started the Game Late.” FlipGive. March 31st, 2016. (Accessed 28 Jan 2018.) http://www.flipgive.com/stories/nfl-greats-who-started-the-game-late |

| ↑17 | Alfie Potts Harmer. “Top 15 Late Bloomers In Soccer History.” TheSportster. 08.24.15. (28 Jan 2018.) http://www.thesportster.com/soccer/top-15-late-bloomers-in-soccer-history/ |

What is going to happen when

What is going to happen when these people get into a random stop by the police and can not walk a perfect line or balance or touch their nose in the only test they have for determining if they’re high on dope? They should be able to carry a medical card that says they suffer from punch-drunk syndrome. Cops have way too much power to determine one guilty just because they say so.

Cops are SUPPOSED to as you

Cops are SUPPOSED to as you if there’s any reason you can’t perform the tests. And that’s why they have multiple tests; if you can’t do one, they can give you another. Or a breathalyzer. Or a blood test.

Seriously, if I were to list “reasons you can’t pass a sobriety test even if you’re stone-cold sober,” punch-drunk syndrome wouldn’t even make the top 20. If I put it on the list at all. Loss of balance isn’t even a major symptom of CTE.