If you’ve followed this blog for a while, you may look at pharmaceutical companies with a bit of skepticism. But the recent news about GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), the pharmaceutical giant that brought you medicines like the antidepressant Paxil, may make you want to swear off prescription drugs altogether. According to the New York Times, between 1999 and 2010, GSK hid data that showed that its diabetes drug Avandia posed severe heart attack risks.

The Avandia issue was first raised in 2007, when a Cleveland Clinic cardiologist did a study based on data that GSK was forced to publish as the result of a lawsuit. The study publicized Avandia’s heart risks. Apparently, when the company released the drug in 1999, it had conducted its own studies to show that Avandia was superior to the competing diabetes drug, Actos, in terms of cardiovascular safety. In fact, the study showed just the opposite. The drug was less safe for the heart than Actos. In fact, it was much less safe. So the company borrowed a page from political scandals past and covered up the data for the next 11 years — this despite the fact that, in most cases, federal law requires results like these to be posted on the company website and turned into federal regulators. Let’s hear it for GSK.

GSK has quite a history. Lest you forget, last year GSK settled a suit because it hid data showing that its antidepressant Paxil caused increased suicidal thoughts and acts in children and teenagers. It was also sued by 49 states in 2006 because it prevented competition by generic versions of Paxil, thereby gouging the Medicare programs in those states. GSK settled out of court, agreeing to pay $14 million. And in 2005, it settled a case in which it was accused of using fraudulent lawsuits to delay generic competitors for its anti-inflammatory drug, Relafen. A fine corporate tradition, indeed!

So why did GSK pursue its corporate tradition of hiding the facts in the case of Avandia? Largely because the company viewed Avandia as essential to its success. The New York Times reported that it obtained documents showing that the company feared a loss of $600 million in sales between 2002 and 2004 alone, if the drug’s safety risks were to “see the light of day outside GSK.” (That amount makes the $14 million settlement mentioned above look like a shrewd business investment.)

Of course, GSK isn’t the only pharmaceutical corporation to be nabbed for fraudulent activity. In 2009, Pfizer paid $2.3 billion to settle accusations that it marketed drugs to physicians illegally, resulting in huge and unnecessary payments by the government. In other words, Medicare and Medicaid paid out large sums for prescriptions for these drugs, which, because of the illegal uses, should not have been reimbursable. Then there was the case of Bayer subsidiary, Cutter Biologicals, and three other companies that paid $600 million in settlements due to allegations that they knowingly sold AIDS infected clotting factor to hemophiliacs. More recently, Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical LLC and Ortho-McNeil-Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc., were sued for illegally marketing the drug Topamax, an anti-epileptic drug, for uses not included on the label. Ortho-McNeil pleaded guilty and paid a fine of $6.4 million. And sister company Ortho-McNeil-Janssen was ordered to pay $74 million because their complicity caused un-reimbursable health claims to have to be paid out by federal and Medicaid programs.

Enough said about the ethics of big Pharma. But if corporate ethics were the only problem with pharmaceutical manufacturers, the solution would be as simple as coming up with appropriate regulation. Unfortunately, the problem has deeper roots, and Avandia provides a good example.

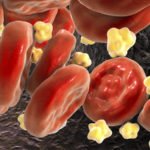

The Avandia advertisements claim that the drug improves the body’s insulin sensitivity so that the body is better able to use insulin to lower blood sugar. While that might seem a positive contribution, the quick-fix approach, unfortunately, leaves much else unaddressed. As I have written before, diabetes is not like other diseases that proceed in a straight-line from a starting point to an end point. Diabetes actually follows multiple, mutually reinforcing paths — an echo effect if you will, with each echo reinforcing and amplifying all the other echoes, or “effects.” This distinction is of vital importance because it mandates multiple points of intervention if you wish to reverse diabetes and not just slow its progression.

But the profit-obsessed pharmaceutical industry focuses not on eliminating or reversing disease, but on delivering solutions that merely suppress symptoms and that can be sold as commodities — pills, injections, technology-based treatments, therapies and so on. Drug companies do not approach bodily dysfunction from a system-wide or holistic point of view. After all, where’s the money in dietary and lifestyle changes, or in the use of non-patentable herbal solutions. If you step back and look at the whole picture, you can see that operating under the premise that disease can best be treated by means of pre-packaged fixes that merely suppress symptoms might lead to poor ethics. In order to make money, these companies need to sell commodities, as opposed to selling better health. But good health doesn’t necessarily respond to commodities. It requires disciplined behavior and often systematic, multi-dimensional approaches. Little wonder, then, that companies that base their livelihood on an approach that can’t really deliver the goods, resort to making up the rules as they go along.

:hc

Noticed that the hypocrits at Consumer Reports have joined the Big Pharma proaganda machine with their report on the “dirty dozen” of herbs. This report on Avandia makes the concern about Kava and others look like childs play, maybe CR is barking up the wrong tree. Oh! I forgot its the Money Tree, stupid me.

This comes as no surprise to me or anyone else who has even marginally cared to keep up with what these crooks are engaged in. The concern is how to get this type of information out to the masses without being written off as just another conspiracy theorist.

Wake up people! You are being conned to unimaginable lengths by the current medical paradigm in many, many ways and in almost all areas of so-called health care. Sad but true, I’m afraid.